You can only buy what is for sale

Life on the sales floor

Working at a large online bike retailer means I am immersed in the constant buzz of the industry. My days revolve around answering riders’ questions, making sales, and trading insights with everyone from seasoned shop veterans to new customers. Even off the clock, I am active in forums and chatting about everything from battery specs to the latest bike trends. Mountain biking is more than my job, it’s what I live and breathe.

Who really sets the trends?

Recently, I have noticed a pattern that rarely gets called out. For example, there is this claim: “E-bikes are getting 600Wh batteries this year because that’s what riders demand.” Honestly, I don’t buy it. Maybe a few riders asked for it, but in reality, Bosch made the decision based on their own priorities: a more appealing look and lighter weight. Bosch deserves credit for convincing manufacturers to market the smaller battery as an advantage—lighter, sleeker, and just as capable thanks to water bottle-sized range extenders. Suddenly, interchangeable batteries disappear, frames get lighter, and every model starts to look more like a standard mountain bike. I get the appeal of good design, but when looks take priority over genuine trail performance, that is a tough pill to swallow.

It is true that Bosch probably has access to far more data than I do—ride stats, charging habits, and real-time analytics from connected bikes. Depending on who you are and where you ride, battery range may or may not matter. Around here, big batteries and capable bikes are what riders want, especially for repeated climbs and descents on steep fire roads. We even inspired the cleverly named Transition Repeater, a bike built for endless laps up a horribly steep road. Still, it is clear to me that companies often steer trends much more than consumers themselves. The narrative that consumer demand alone shapes the bike industry sounds nice, but reality is full of hidden trade-offs and company decisions that shape what ends up in shops. In the current e-bike arms race, battery and motor choices are everything. Right now, in 2025, offering a Shimano motor just is not competitive. Bosch, DJI, and Specialized are making major moves, with TQ and Mahle not far behind. Who’s buying an Amflow because they want that frame???

How trends really change the bike world

When you look at how bike design happens, you realize most of these big decisions come from a surprisingly small group—sometimes just one or two engineers. Whether or not something becomes a best-seller is only partly a sign of quality. I remember the way one or two opinion leaders sparked big debates about wheel size. The rise of 27.5-inch wheels pushed 26-inch bikes out, and it did not happen because the majority of riders were asking for it. Then the industry rapidly shifted once again, and 29ers became the standard, making 27.5 less common overnight. Now, we are seeing the first arrivals of 32-inch wheels, the next potential “must-have,” despite little widespread rider demand. Each of these changes started with a small group, sometimes just a few influential figures, but they ended up reshaping the entire sport—even when most everyday riders were happy with what they already had. Chasing the next big thing often overwhelms people with options, but it does not always guarantee a better ride. Plus-size tires are a perfect example: there was hype for a moment, but they disappeared just as fast.

The cost of chasing innovation

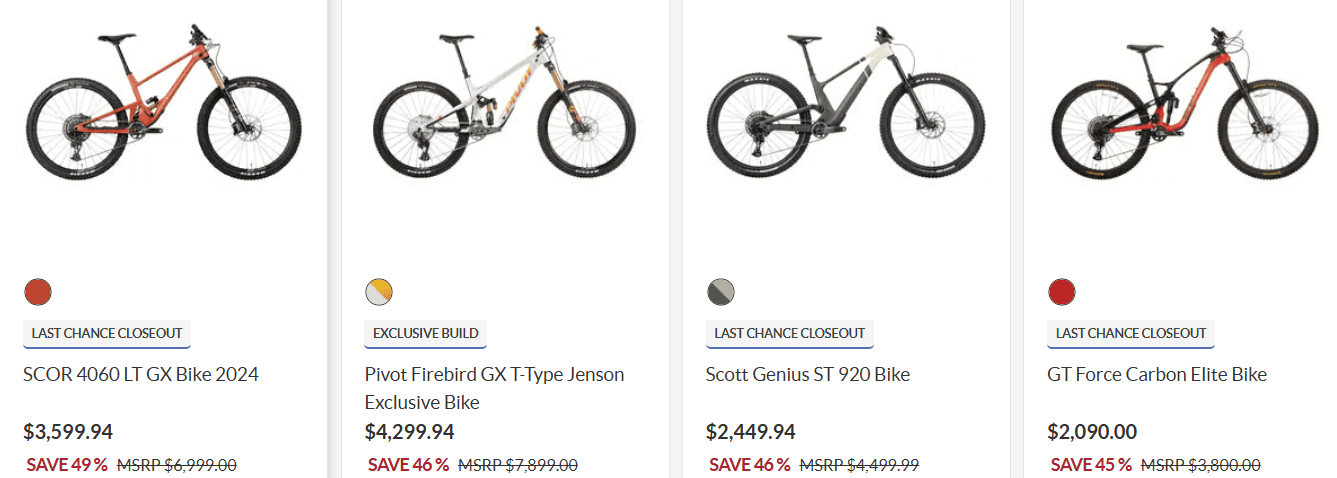

Innovation for innovation’s sake can even hurt the industry’s foundations. Brands pour more resources into e-bikes, and in some cases, they are outselling traditional mountain bikes. New tech is exciting, but does it always make riding better? Not necessarily. At the end of the day, companies aim to sell bikes; satisfying riders is sometimes a side effect, not the main driver. Occasionally, true consumer demand leads. DJI’s (sorry, Avinox…) e-bike motors are a good example, but most of the time it’s companies betting on what will sell next. With so many variables—geometry, components, prestige, warranty, price, and appearance in the mix, it’s often a mystery why one bike soars and another fizzles. Riders like to justify their picks, but emotions usually seal the deal.

Are consumer choices an illusion?

Consumer choice looks broad at first glance, but it’s often more limited than people think. Look at Ari, formerly Fezzari. Their 2025 Timp Peak has all the right features: Bosch Gen 5 motor, choice of 600 or 800Wh batteries, water bottle compatibility, range extender, swappable batteries, and room for a long dropper post. It competes directly with the Santa Cruz Bullit, which is mainly lighter due to a smaller battery. Yet, Ari just isn’t considered “cool.” Skilled riders still gravitate to what looks good or fits in socially, overlooking what the spec sheet says. Even when Ari nails the product, it risks being ignored. Meanwhile, riders complain online about Santa Cruz putting just a 600Wh battery and limited fork compatibility on a theoretically downhill-focused bike, without realizing the Ari Timp Peak quietly solves every one of those issues. There are a handful of other bikes that check some of the same boxes, but a number of small factors could easily steer a rider away from making a more exotic choice.

As new models roll out for 2025, we will learn which battery size actually resonates with riders. But when brands only offer the slimmer, more conservative option, it does not always reflect what people truly want; it is just the only option on the shelf that meets enough of the criteria to make sense. Of course everyone will be happy to have more range, more power, and lighter weight. No one is saying no to lighter ebikes, but let’s not kid ourselves that the 600wh battery is what the people asked for. This is what brands have decided to sell.

Conclusion: A compromise in every choice

Picking the right bike involves real compromise. Starting a brand is hardly possible, and buying one means wrestling with the choices made by someone else. The industry, by and large, trusts in a single engineer’s vision or a small design team, not a broad rider consensus or extensive real-world testing. A few brands, like Kavenz, have tried truly collaborative design, but those are the exception. The mix of variety and limitation is what keeps the bike world interesting, even if so-called consumer demand is often just a myth. Slow, incremental change, and occasional big swings that miss, are simply the result of a system where a handful of people decide what the rest of us ride—sometimes for the better, but not always. I’d love to see more integration of true testing and feedback and iteration rather than a mock up on the computer.